Mystery of The Enigmatic Honjo Masamune Sword

The Honjo Masamune is the ultimate samurai sword. In Japan it’s regarded as a national treasure, a thing of beauty shaped by fire and born of water, forged centuries ago by master swordsmith Masamune. Proven in battle for centuries, legend tells of a just blade, discerning and honorable. It was venerated as the hereditary sword of power by the ruling Shoguns. Passed from generation to generation for seven-hundred years. But in the aftermath of the second World War, it suddenly disappeared. Records tell us a mysterious U.S. Sergeant took it to be destroyed, but some say he saved it and took it home to America. Now worth millions of dollars, experts believe it may still be out there. This is the story of the ancient legendary Honjo Masamune, lost sword of the samurai.

In the late 13th century, the rulers of the Kamakura province near Tokyo had a serious problem, the invading Mongol hordes of Kublai Khan. Under the onslaught, their weapons simply weren’t up to the task, and would often break against the toughened Mongol armor. To solve this problem, they turned to swordsmith Gorō Nyūdō Masamune. Masamune’s task was to redesign the Japanese sword to withstand the armor and kill the Mongol invaders. Masamune developed techniques that have never been surpassed. First, he beat red hot high carbon steel into a thick rectangular billet, then cutting and folding it again and again, he forged a blade composed of over 30,000 layers. To the thick back edge and the thin cutting edge he gave very different properties, and these were born not from the heat of the fire, but how the steel cooled in water.

Mongol invasion of Japan

The thicker, heavier back edge gave up it’s heat more slowly. This changed the structure of the iron itself, making it far less hard but more flexible than the vulnerable sharp edge. In battle, the thin edge was used offensively to cut. It was rigid and razor sharp. And the back used defensively as a shield, it’s flexible spine absorbing impact. But to withstand the Mongol armor, Masamune also made it’s blades broader from edge to back for added strength. The point was made longer to pierce, and the hardened edge deeper to aid repair. And so Masamune brought the samurai sword to the peek of perfection, exemplified by the Honjo Masamune. Not just a weapon, but a work of art, an object of true beauty. Masamune’s name still resonates throughout Japan today.

Over the centuries, many legends have been told about the great Masamune and the magical qualities of his swords. One of Masamune’s pupils thought that after many years training he had surpassed his master. To test the quality of their respective blades, they suspended them in a stream. The student’s blade was so sharp that it cut leaves and twigs, everything in it’s path. Masamune’s blade while just as sharp cut nothing. The student claimed victory, but a bystander disagreed. He observed that Masamune’s blade did not cut needlessly. It was discerning and honorable, a just blade.

His finest work, the Honjo Masamune, was primarily a weapon for cutting human flesh, and the samurai would develop a very practical method for testing blades. For a fee, an official tester would use a blade on a corpse from the execution grounds and report back to the owner on how it cut and behaved, and how many bodies it cut. The edge was sharp and the back strong, but yet another key property made the sword so deadly, it’s curved edge which cut flesh with ease.

As a permanent record, the test results would be carved into the sword’s tang under the mounted grip. History doesn’t record precisely when he drew from his furnace the greatest blade he ever made. Around the year 1,300 is the closest year anyone can say. Nothing is known of it’s early life or battles, who wore it proudly in their belt or who inherited it over the centuries. Such a fine sword would have played an important role in the rigid social structure of Japan, in which everyone knew their place.

The powerful land-owning lords, the daimyos, were protected by the knightly class, the samurai. The name samurai literally means one who serves. The sword was an essential part of the samurai’s dress, the uniform of his class. The longsword was a large part of who he was. The sword was something more than just a weapon, it was his most prized possession. It was described as the soul of the samurai. Just as a samurai’s life belonged to his lord, lives of those with a lower rank, farmers and peasants, belong to him. The samurai were allowed to cut down a civilian for an insulting gesture.

Samurai wielding a Japanese Katana sword and wakizashi (daisho)

The Honjo Masamune first enters recorded history when 300 years after it was made it received it’s name. In the 16th century, general Honjo Shigenaga was attacked by an enemy with Masamune’s masterpiece. The sword had already claimed a number of trophy heads that day, but general Honjo Shigenaga prevailed, and finally victorious, took the sword as his prize. From then on, it bares his name.

Soon afterwards, general Shigenaga was ordered to Fushimi castle, but short of money he sold the now priceless sword for 13 large gold coins. At today’s gold prices, around 3,000 dollars. It was now that the Honjo Masamune was transformed from a valued weapon to a priceless symbol of absolute power. The superlative sword became the ultimate gift to pass up the social ladder to nobles of ascending rank as a token of esteem. Eventually it was received in tribute by warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu. With the Honjo Masamune at his side, Tokugawa Ieyasu was about to change the course of Japanese history.

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Japan was being torn apart by civil war, daimyo against daimyo, samurai against samurai, each fighting loyally for his lord to the death. Finally in 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu amassed enough military power to seize overall control. He made the emperor a mere figurehead. Ieyasu himself would rule Japan as military dictator, he would be the shogun. The Tokugawa shogunate brought 250 years of peace to Japan and their ceremonial sword was the Honjo Masamune. Over the centuries, the hereditary sword of the Shoguns was passed from generation to generation. Even after the Tokugawa’s fell from power in 1868, the great sword continued to be handed down within the aristocratic family into the 20th century. In 1939 in Tokyo, it was designated a Japanese national treasure, a survivor of 700 years of turbulent history. It was only in the upheaval of the second World War that the mystery of the Honjo Masamune began, when it disappeared.

Japan entered World War II in 1941 with a surprise attack on the U.S. Navy anchored at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. As Japan poured millions of troops into battle, the high command boosted recruitment and morale by fostering the ideals of Japan’s ancient past. This ideal was Bushido, the way of the warrior and the heroic exploits of the samurai. Every officer, sergeant, and corporal had to wear a sword as part of his uniform. The sheer number required was huge, so these modern military swords were not hand-beaten by master craftsmen in the traditional way, but mass-produced in factories from ordinary steel. By the second World War there are estimated to have been as many as two-million swords worn by the Japanese military. The symbolism of the sword continued to be promoted in Japanese propaganda throughout World War II.

B-29 releasing incendiary bombs on Yokohama

For the Japanese, war was a fight to the death. The emperor and the government could not permit surrender. On August the 6th and 9th 1945, an American B-29 aircraft dropped a bomb on two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Just six days later, the Japanese had to bear the unbearable. They surrendered. Across the radio comes the voice of the emperor which nobody’s heard before. The message is clear, through his weak voice everyone can gather that they’ve lost. At the end of the second World War, the average Japanese person would have been totally devastated by having suffered defeat, the loss of face, but on the other hand the war was over and the hardship they had been through was finished.

Not for the first time in Japanese history, the emperor had to move aside for a powerful shogun. Shogun is a very old title in Japanese history. It means not just military commander but supreme dictator, and the man the United States sent to rule the now occupied Japan was certainly that, five-star General Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur officially accepted the Japanese surrender in a ceremony aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on the 2nd of September 1945.

General Douglas MacArthur

As soon as the surrender was signed, MacArthur as supreme commander for the Allied powers set to work. He issued SCAP general order number one, the immediate surrender of all Japanese armed forces. MacArthur demanded they cease hostilities and lay down their arms. MacArthur’s plan was to make sure Japan could never wage war again. Total demilitarization and disarmament were paramount. MacArthur soon destroyed hundreds of ships and thousands of planes, but what should he do with all those swords? Every Japanese officer, sergeant, and corporal carried one at his side. There were millions of them, but MacArthur was determined to collect every one. Not because the swords were a military threat, but because of their enduring symbolic importance.

All over the Pacific, surrender ceremonies were organized by the victorious Allies. On parade grounds in Sumatra Burma and Malaya, Japanese soldiers suffered the humiliation of surrendering their treasured swords to the Americans. What the Allies didn’t realize were that some of the swords were not mass-produced weapons, but handcrafted antiques of tremendous value. Surrendering a venerable family heirloom was especially painful. Hundreds of thousands of swords were surrendered. But what to do with them? Some were awarded to Allied officers and some to civilians who had distinguished themselves in the war effort. To one a crude mass-produced blade, to another perhaps a centuries-old work of art. The American officers didn’t know or care. Most of the swords were not given away, but were destroyed.

A Japanese general surrenders his sword in 1945

The SCAP instruction for disarmament applied not only to front line soldiers but the people of Japan at home too, even swords in private hands. The Honjo Masamune in the Tokugawa mansion in Tokyo was no exception. The order to collect all swords meant just that. These seizures were indiscriminate. Family heirlooms decorating homes and masterpieces in collections were commandeered as quickly as military blades. The owners of swords were instructed to take them to collection points such as police stations. Even the artistocratic Tokugawa family who’s Shoguns once ruled Japan were not exempt. The SCAP instructions were law, and they were ordered to relinquish all of their fine swords, including the legendary Honjo Masamune. In Japan there was outrage, would they really have to give it up to the Americans who appreciated nothing of it’s history or symbolism?

Influential people, collectors, and museum curators were soon complaining to SCAP about this assault on the Japanese heritage. A representative of the Tokyo Museum met military police commander Victor C. Cadwell of the US Eighth Army, the officer in charge of weapons collection. They explained that some swords were ancient works of an almost forgotten art, like the cathedrals of the west. A vivid symbol that was an extension of the samurai himself, influencing Japanese art and literature. They were not military weapons at all. Treasures like the Honjo Masamune were art swords. They succeeded and convinced Colonel Cadwell that Japanese swords were not simply wartime weapons and should no longer be treated as such. SCAP instruction 12 tried to clarify the situation by letting treasured heirlooms stay with their owners, but Cadwell didn’t have the final word. This instruction was later redacted, and all swords were yet again up for seizure.

Some families protected their heirlooms by deceiving the Americans. Certain families in Japan deliberately acquired very poor quality swords and hid their better swords because they knew they were going to be taken by the victors. But the Tokugawa family did no such thing, they took a very different honorable course and accepted the latest edict from SCAP. Just before Christmas 1945, the last known owner of the Honjo Masamune, Tokugawa Iemasa, a descendant of the Shoguns, obeyed the law and delivered the family swords to Mejiro police station. Tokugawa Iemasa handed in 15 swords, bundled all together. Among them was the finest sword ever made, the Honjo Masamune. Mr. Tokugawa never saw the great family sword again. The Honjo Masamune disappeared and entered the realm of conjecture and mystery.

Mejiro Police Station

The first clue to what became of the lost sword of the samurai appeared in New York, 20 years after the end of World War II. The August 1966 edition of Saga, an American adventure and mystery magazine contained an article listing the Japanese national treasures that went missing after the war. The list of 14 swords included the Honjo Masamune. There in black and white it recorded that a sergeant Coldy Bimore of the seventh U.S. Cavalry had collected it from the police station at Mejiro. But how reliable was this record? What is undoubtedly true is that the 7th cavalry patrols were in Tokyo and did make inventories of all arsenals, factories, barracks, and storage depots. They also disposed of munitions and conducted patrols in search of hidden Japanese weapons including swords. This corroborates the Saga magazine article.

The next question is, did sergeant Coldy Bimore take the sword from the police station? Unfortunately all police records for the period in question are lost, but there is another source, the Japanese Department of Education. Their records at the time make it clear that the Honjo Masamune certainly was taken from the Mejiro police station by sergeant Bimore, but where did he take it?

All over Japan, collected swords were piled high in warehouses before being dumped at sea or melted down for scrap iron. In Tokyo, for sergeant Coldy Bimore, storage was at the Akabane depot. To avoid the destruction of art swords, every blade at Akabane was scrutinized by an inspection committee. It was a big success and nearly 5,000 swords were identified as important cultural artifacts and returned to their owners, but the Honjo Masamune was not among them. Was it fed to the furnace and destroyed, or did Coldy Bimore keep it for himself?

US Army Troops with Japanese Swords

What is certainly true is that the American army operated an official war trophy system. A GI who had taken part in the Pacific War could with the correct permission slip take home one enemy gun and one sword as personal souvenirs. Most of these returning men were carrying mass produced military swords, nothing special, but some GI’s unknowingly had centuries-old works of art of great cultural and monetary value. It’s very possible that the Honjo Masamune was taken by Coldy Bimore as his personal momento. If this was true, the question then became when did sergeant Bimore get shipped home, and did he carry the Honjo Masamune with him?

At this point the trail becomes even more obscured. Seventh cavalry records should reveal when sergeant Coldy Bimore left Japan and when he arrived home but the seventh cavalry veteran’s association lists no one by that name. Does that mean there never was a Coldy Bimore? The facts were more complicated. The Saga magazine article contains another clue. It describes the name Coldy Bimore as phonetic. This indicated it’s a translation from English into Japanese. The strange name Coldy Bimore may be inaccurate after-all.

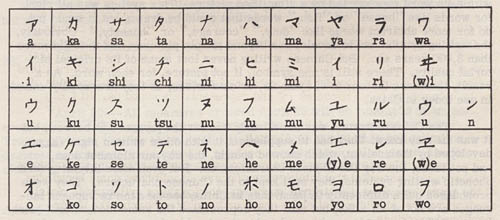

The Japanese have developed phonetic alphabets to help transcode English and other languages. The characters are not words as in Japanese but represent particular sounds. This system of transliteration is far from perfect, as Japanese sounds don’t appear in English, and English sounds have no Japanese equivalent. The name may not be Coldy Bimore, but something that sounds a bit like it.

Some examples of Katakana (Phonetic Japanese)

So was there a seventh cavalry sergeant in Tokyo on the 18th of January 1946 with a name similar to Coldy Bimore? Unfortunately the SCAP records of lowly sergeants have been routinely destroyed. The true name of the sergeant will most likely never be found. But even so, many believe that the Honjo Masamune could still turn up. In the years since the war, Americans began to understand the prestige and value of fine Japanese swords properly. President Truman was given a 650 years old sword in a 350 year old silk wrapping as a war souvenir.

The Allied occupation of Japan continued until 1952 and the influx of swords to America after the second World War was like a tsunami. For the handful of knowledgeable sword enthusiasts who recognized the characteristics which made a blade great, there was the opportunity to make a lot of money. Dealers discovered that hidden in the stream of confiscated weapons there were historically important swords now scattered all over the United States. Could the Honjo Masamune be among them? Since World War II there have been thousands of ads placed in newspapers all over the U.S. offering to buy Japanese swords. These were the days when a fine collection could still be acquired very cheaply.

As this market developed, some important art swords did occasionally turn up. Avid collector Clive Sinclair came by a sword when it surfaced in just this way. Wonderfully preserved, it was made especially for the Shogun’s chief test cutter. It turned up in an antique fair, swapped hands for 500 dollars, and is now a priceless antique. Could this one day happen to the Honjo Masamune? If it did emerge from someone’s attic, how could it be recognized? There is a tell-tale way of knowing. 700 years ago, when Masamune plunged the hot blade into cold water, he gave birth to a razor sharp weapon, but he also gave the Honjo Masamune a unique signature.

Line drawings of the unique hamon of the Honjo Masamune

For centuries it was customary for an artist to meticulously draw the unique pattern on the edge of a fine sword, the hamon. When in 1939, the Japanese declared the Honjo Masamune a national treasure, such fine detailed drawings of the hamon were made. If the Honjo Masamune ever appeared at an antique fair or auction, there could be no mistake. It’s fingerprints have been taken. But any lucky finder in the U.S. would face a catch 22. For a collector to be certain and for it’s identity to be official, the Honjo Masamune would have to be sent to Japan for a rigorous examination by Japanese experts to be verified. So if anyone did find it, they would have every incentive to keep it secret for fear of losing it.

Whatever the case, the whereabouts of the Honjo Masamune remains a complete mystery to this day. Anyone trying to trace it faces huge obstacles. The few clues that exist are sparse. The identity of the elusive cavalry sergeant is still a mystery. Precisely what happened that day at the Mejiro police station may never be known. If only we had the paperwork or even a signature, the Honjo Masamune might yet be found. It’s one of the ironies of this story that the Honjo Masamune could have possibly been kept after all. If the Tokugawas had only waited just a few months until the law was changed, they wouldn’t have had to give it up.

There is another irony, because it is lost, the Honjo Masamune has been transformed from a historical artifact to a thing of legend. The legend will only ever grow stronger, until more evidence can establish where it is, or whether it has been destroyed. Anyone with a love of Japanese swords can never give up hope. While a treasure such as the Honjo Masamune remains lost, stories will be told of it’s possible location, and people will dream of it and hunt for it. The lost sword of the samurai.

Best Sellers

- Regular Price

- from $199.99

- Sale Price

- from $199.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $319.00

- Sale Price

- from $319.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $219.00

- Sale Price

- from $219.00

- Regular Price

-

$0.00

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $649.00

- Sale Price

- from $649.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $339.00

- Sale Price

- from $339.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $269.00

- Sale Price

- from $269.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $239.00

- Sale Price

- from $239.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $359.00

- Sale Price

- from $359.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $539.00

- Sale Price

- from $539.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $384.00

- Sale Price

- from $384.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per