History of Samurai and the Virtues of Bushido

The origins of this fierce warrior class, the samurai, are to be found at the very beginning of Japanese history. These mounted warriors galloped into history during the reign of emperor Tenmu, whose army of peasants, armed with crossbows, was failing to subdue the mobile cavalry of the unruly tribes of the north. Tribes which may have included Ainu, the indigenous peoples of Japan. And so, emperor Tenmu made a fateful decision. He dissolved his ineffective national army. Instead, he ordered local chieftains to create bands of elite mounted warriors to enforce his authority in rural areas and to challenge the northern tribes. These were the first samurai.

The word samurai means to serve, and this is how they began, as warriors serving the emperor. While the imperial court prayed to the gods for their success, the mounted warriors rode out to hunt down the proud barbarians of the north once and for all. But the tribesman were crafty fighters, adept at ambush. The warriors often had to forsake their bows and fight with their straight swords, swords which in the heat of battle when chopping downward from horseback, snapped in two. The samurai needed better swords. According to legend, a swordsmith named Amakuni rose to the challenge.

Mounted Samurai

One day, standing in his doorway, Amakuni noticed that the warriors returning from battle were carrying broken swords, ones that he had forged. The emperor himself passed by and frowned at the disgraced smith. Amakuni’s problem was the classic problem of swordsmiths all around the world. How do you make a sword that is very sharp but also tough enough not to break? When working with steel, a swordsmith must control three things: the rate of cooling, the carbon content, and elimination of impurities. If he cools red-hot metal too quickly, it becomes hard enough to sharpen to a fine edge, but also very brittle and liable to snap in two. If he cools the metal too slowly, the sword will be very tough and flexible but won’t take a sharp edge.

Amakuni experimented until he had developed the techniques to solve these problems. He had selected the finest iron ore and carefully refined it, adding just the proper amount of carbon to the steel. He then broke the iron block and reassembled the pieces like a puzzle to make another block to further purify the metal. The block was then folded and hammered out over and over to distribute the carbon evenly and to eliminate impurities that might create weak spots in the finished sword.

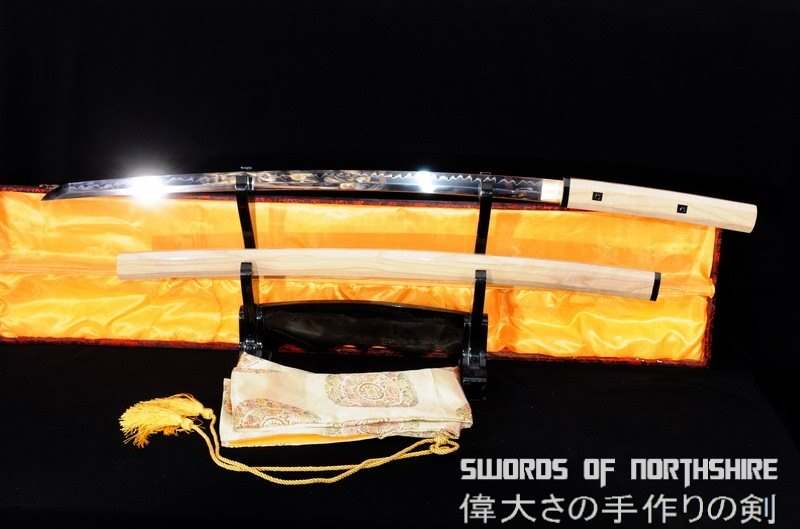

Next, he lengthened the block into a blade and gave the sword a curve to make it slice more effectively on the downward stroke from horseback. What he did next was one of the secrets of the samurai sword. He covered the body of the sword with clay, and left only the edge exposed. He then plunged the hot blade into water to quench it. The unprotected edge cooled quickly, becoming very hard so it could be sharpened to a fine edge, while the clay covering allowed the body of the blade to cool more slowly, and remain softer and more flexible. This produced a distinctive wavy pattern along the cutting edge called the hamon, the mark of a true hand-crafted samurai sword.

When the warriors returned from battle the following year, the emperor stopped to tell the smith “You are a master swordmaker, none of your swords have failed”. These early curved swords were called tachi, and were worn edge-downward from the belt. Armed with these swords, the samurai increased in power and in pride. From the 12th century onwards, samurai began to serve as samurai lords and no other.

The capital was moved to the sacred city of Kyoto, where Kanmu, the 50th emperor of Japan, built a magnificent new palace, an impressive symbol of imperial authority. But while the samurai gained in power, imperial power gradually weakened. One samurai named Taira no Masakado even dared to proclaim himself emperor. He was defeated, but for most of the next 1,000 years the samurai would fight amongst themselves to dominate the imperial court. But the samurai were not the only ones fighting for control of the emperor. Monks too became warriors in their quest for power.

Sohei Warrior Monks

Today a peaceful mountain retreat, a temple on Mount Hiei was once the headquarters of the largest, and most formidable army in Japan, an army of warrior monks called the Sohei. At it’s height, the temple complex boasted over 3,000 buildings. Wielding their fierce naginatas, a huge war party of Sohei monks would often flow down into the city of Kyoto to press their demands for privileges on the imperial court.

Monks are supposedly peaceful, but the Sohei monks were legendary warriors. One of the most impressive feats of martial history took place at Uji bridge in the year 1180. A band of monks, hopelessly outnumbered by attacking samurai, tore up the planks of the bridge to defend their retreat. One of the monks climbed up on the bridges railings, and while whirling his naginata like a propellor, defended the arrows being shot at him. With this, he was dubbed Tajima, the arrow cutter.

Despite their fighting prowess, the monks were finally no match for the powerful samurai clans who eventually tamed them. In the 13th century, the most powerful clan of all, the Taira, were at war with their arch enemies, the Minamoto. These were the classic battles of early samurai history, full of pomp and ritual. First, commanders would gallop out and proudly announce their ancestry, proclaim their greatness as warriors, and throw the vilest insult they could think of at their opponent. Next, they shot their arrows and charged each other, hoping to dispatch their foe with a single stroke of their sword. Onlooking warriors would not stain the honor of the combatants by lending any help.

For the samurai, honor was everything. More precious than life itself. They would kill or die in an instant to defend it. And there was a very practical reason for this obsession with honor. A samurai’s status and his lands were not protected by law, only granted by his lord. Failure or defeat in battle meant loss of his land and status, reducing him and his descendants instantly to peasants. His easily offended honor and incredible loyalty was in essence, pure job insecurity. And so, the samurai brought back enemy heads after a battle which they presented to their lords as proof of a kill. Their lord rewarded them with land and titles. If a samurai were defeated in battle, but survived with his head intact, he often preferred to take his own life rather than face the disgrace of his failure.

One early suicide was done with such style and grace that it was to provide a model for noble and heroic ritual suicides for centuries to come. After one fearsome battle with the Taira clan, the defeated samurai Minamoto Yorimasa retreated inside a temple while his sons defended the gate outside. He then penned his death poem on a war fan before committing ritual suicide. Yorimasa killed himself in the most painful and thus most heroic way possible, by plunging his short sword into his abdomen. This act took more than just courage or practical calculation. It took supreme conviction.

One group of samurai failed to defend a castle for their lord, and rather than accept defeat, 384 of these warriors committed suicide in the main hall of the castle. Their lord honored them by taking the floor of the hall and making it the ceiling of a Buddhist temple, raising their act of suicide to a spiritual plane. What possessed the samurai to take their own lives in such a slow and painful fashion?

Blood-stained ceiling in Kyoto's Chitenjo temple

Suicide was a rational and practical choice, preferable to the dishonor that would doom not only a samurai himself, but also his family and descendants to the brutal life of a peasant or high-way robber. The samurai were trained from childhood to welcome an honorable death. They were taught the zen Buddhist belief that life was but a brief illusion, a flash of lightning, a bubble in a stream. In this warrior’s mind the very point of living was a noble death, preferably on the battlefield with honor, but failing that, by his own hand. A noble death became more than dignified and beautiful, it was seen as an almost holy act, a release from the cycle of life’s suffering.

It was this total lack of fear that allowed the samurai of the Minamoto clan to triumph over the Taira in a desperate sea battle in the year 1192. The Minamoto leader Yoritomo was not content merely to be the military leader of Japan. He rejected the titles given to him by the emperor and established his own government. Yoritomo became shogun, military dictator and the first samurai ruler of Japan. He chose the easily defended town of Kamakura, far from Kyoto, to be his headquarters.

Yoritomo built a giant Buddha, now famous throughout the world, but his real legacy was the code that he required his warriors to follow. He ordered his samurai to live lives of simple frugality, to have no fear of death, and to serve him with unswerving loyalty. During this peaceful age, the best swords were the products of imperial support for the art of swordmaking. The cloistered emperor Go-Toba himself was an accomplished swordsmith.

Yoritomo's giant Buddha Statue in Kotokuin Shrine

Emperor Go-Toba called in the best smiths of Japan and had them restudy all swordmaking methods of the past. Their great accomplishment was to develop a new two-piece body for the blade. Until this time, swords were made from a single piece of high carbon steel. These imperial smiths soon learned to insert a soft core of low-carbon steel into the sword. The sword of the samurai became even more flexible while retaining it’s razor-sharp edge. This time of peace was the age of the classical samurai and the golden age of the Japanese sword, but this fragile peace was soon shattered.

In the year 1274, a terrible danger appeared on the horizon, the Mongol hordes of Kublai Khan in an invasion fleet of over 800 ships with 30,000 seasoned battle troops. The samurai charged down onto the beach and yelled out their customary challenge for a battle. Their challenges were answered with hails of poisoned arrows and gunpowder bombs. The Mongols were surprised however at the desperate strength of the samurai and their sharp swords that somehow were able to cut through their armor.

Then suddenly a terrible storm swept into the battle. The mongol fleet was destroyed by a typhoon. Expecting a second invasion, the Japanese constructed an enormous defensive wall on the beach where they expected the Mongols to land. Sure enough they came again, this time with 4,000 ships and over 200,000 men. The samurai defended the beach fiercely, attempting to prevent the Mongol force from landing. But then amazingly for the second time, a typhoon swept in destroying the entire mongol fleet. Two-thirds of the Mongol invaders perished. Thus Japan was saved from invasion, twice. This convinced the Japanese that their land was protected by the gods, and they honored the storm with the name of Kamikaze, or divine wind.

Kamikaze - Divine wind during the Mongol invasion of Japan

The samurai learned a great deal from their battles with the Mongols. On the beaches, the blade, not the spur, had saved the day. And so the stress on mounted archery lessened, and over the next century the samurai became a swordsman who fought on foot. Because the deep curve of the long tachi sword made it difficult to draw, it was replaced by the shorter infantry K Katana sword which was worn edge upright so the samurai could draw and slash in a single stroke.

The battles with the Mongols taught the samurai something else. The tempered edges of their supposedly perfect swords often chipped. Correcting this defect was the triumph of one of the greatest swordsmiths who ever lived, Masamune. With his new forging techniques, he achieved a perfect balance between hardness of the blade and flexibility. Masamune heated his blades over the critical temperature of 750 degrees celsius. Next he welded three pieces of steel of different carbon content together into a single blade. The samurai sword had at last been perfected. Japanese swordsmiths all began to copy Masamune’s methods. The swords he made were legendary for the sharpness of their cutting edge. So sharp were these swords that they apparently made the bearer go mad with bloodlust, almost as if the very effectiveness of the blade forced it to be used to kill. Armed with these perfect swords, the samurai could almost magically cut through their enemy in a single fluid stroke.

The culmination of a samurai’s rigorous training became the ability without conscious thought to execute this perfect attacking stroke. This stroke could only be perfectly executed if it were done with an empty mind. The no mind of Zen Buddhism. Practicing this stroke became a kind of meditation, a way to develop discipline and character. Some say you can see a pale residual image of this perfect no mind stroke at Japanese driving ranges. In the swings of countless golfers who spend endless hours trying to perfect their stroke, even though they rarely if ever play on the golf course.

One samurai in particular was held up as the ultimate example of the virtue of loyalty to one’s master, Kusunoki Masashige. So total was his loyalty that the emperor was able to return from exile, defeat the shogun in Kamakura, and reassume power. But this legendary samurai loyalty usually had it’s limits. The temptation of power was too strong. In the century after the Mongol invasion, proud samurai warlords, many with imperial blood in their veins, aspired to be shogun. The prize was there for the taking for any warlord who could seize and hold it.

This led to the age of the country at war, the inevitable result of the previous 1,000 years of Japanese feudalism. A war of all against all engulfed Japan. The name of the samurai became synonymous with the most flagrant examples of brutality. New and more formidable castles were raised. Treachery and cowardice were widespread and there was a great reliance on espionage. Samurai, with their code of honor, could not be expected to undertake these covert tasks. To fill this niche, there flourished in the small mountain village of Iga, a group of secret warriors. The powers of the ninja have been shrouded in a mystique of incredible proportions. For protection against these covert mercenaries, many samurai castles and houses built nightingale floors, specially constructed to loudly squeak when trod upon, a security system designed to defend against the ninja.

With a decline in the warrior ethic came a decline in sword quality. Mass-production resulted in many inferior blades. It was during this period of intense warfare that a new weapon arrived on the battlefield, a weapon that would end forever the dominance of the classical warrior. In 1542, a ship arrived on the shores of Japan. On board were three Portuguese who became the first westerners to land on Japanese soil. They were strange and exotic but what really caught the attention of the Japanese were the guns that they carried. The samurai understood immediately that guns threatened their very existence. Their ancestors always had known who they killed and who defeated them. With guns, how could they prove their valor to their lord? How could he reward courage? Even lowly merchants and peasants could fight with these cowardly weapons.

Tradition soon gave way to technology. Many swordsmiths became gunsmiths. Eventually Japan was actually manufacturing better and a larger amount of guns then any European country. Guns, along with professional military organizations, finally ended the age of total war. Three great generals each contributed in his own way to a unified Japan. The first of these unifiers, Oda Nobunaga, who was born a peasant, eagerly took advantage of the superior supply of gunpowder available in his province. With his fearsome musket regiment, Nobunaga led an attack on Takeda Shingen.

Facing Nobunaga’s troops in the field were the mounted samurai of Takeda, proud inheritors of the Minamoto classical tradition, a tradition that left them no choice but to attack. Nobunaga’s musketeers moved to the front lines, a place of honor, traditionally reserved for the best swordsman. The Takeda cavalry charged down the hill only to be met with the deafening roar of 3,000 guns firing at once. While one rank fired, two reloaded. This was the first time that this devastating strategy, called rolling volley fire, had been used in world history. When the smoke cleared, 10,000 Takeda samurai lay dead on the field. Japan would never be the same.

For all of it’s lethal beauty, it’s noble tradition and the incredible skill required to wield it, even in the hands of the most courageous samurai a sword could not compete with a bullet fired from a gun in the hands of an uncultured peasant soldier. In the 16th century on the strength of his guns, Nobunaga began to unify Japan’s warring samurai clans. But at the height of his power, the ruthless and brutal Nobunaga was assassinated by one of his own generals. His death was avenged by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, his clever lieutenant who laid the head of Nobunaga’s killer on the grave of his slain commander. Hideyoshi was not just a brilliant soldier. He was also a shrewd judge of human nature, a master of diplomacy and compromise.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

He soon became the unrivaled master of all Japan. In 1588, Hideyoshi instigated the great sword hunt. He collected guns and swords from all the peasants and melted them down to make an enormous bell and a giant statue of the Buddha. The statue is gone, only a piece of the Buddha’s nose remaining, but the enormous bell famous throughout Japan still exists today. The tolling of this great bell signaled the end of social mobility in Japan. From this time forward, one had to be born a samurai to wear the sword. Never again would a peasant rise up to usurp power as Hideyoshi himself had done.

Hideyoshi’s next project was to build a formidable castle at Osaka, designed to guard his legacy. His ambition did not stop there. Hideyoshi decided he wanted to rule an empire. To him there was only one thing bigger than Japan, and that was China. The invasion did not go well. Meanwhile the third unifier, Ieyasu Tokugawa, a powerful lord who traced his ancestry back to the first shogun, pulled back to his own provinces during Hideyoshi’s invasion of China and bided his time, strengthening his position. After Hideyoshi’s death, Tokugawa had the largest standing army in Japan. Hideyoshi had made Tokugawa swear to be loyal to his heir, an oath that Tokugawa broke when he attacked the heir’s forces at Osaka castle.

Despite it’s massive walls, the castle was no match for Tokugawa’s superior siege guns and cannons. Tokugawa in his turn became lord of all Japan. The last and greatest of the three generals had finally brought the bloody civil wars to an end. Once in absolute power and control, Tokugawa refashioned Japan into his ideal of an inflexible and rigidly structured society. He expelled foreigners and amazingly outlawed all guns. Japan went back to the sword. But in this unprecedented time of peace, the samurai no longer had a reason to use them.

Society in the Tokugawa period

There were no more battles, and the Tokugawa government outlawed sword duels and vendettas among the samurai. Domestic peace had a serious eroding effect on the warrior ideal Tokugawa tried to instill in his samurai. They ate, drank, played games, and dreamt of glory in times gone by. The samurai however were able to take solace in the law that required them to wear the daisho, a two sword combination. This set of swords served as a distinctive badge that indicated their privileged social status, but these swords were mostly symbolic. Almost anyone of high rank began wearing them to denote their status.

In this long age of peace, the production of swords came almost to a standstill, whereas the creation of mounting and fittings for swords became a prosperous business. Precious metals were used to create extremely elaborate decorations for swords. Small pieces of metal were attached to the sword’s hilt under the silk wrapping. These were called menuki and they became intricate miniature sculptures. Also more attention was given to the external beautification of the blade itself. Designing the hamon, the pattern along the edge of the blade, became an art of it’s own, a kind of abstract painting on a steel canvas. Different smiths created signature hamon patterns on their swords such as mountains, cherry blossoms, the waves of the ocean.

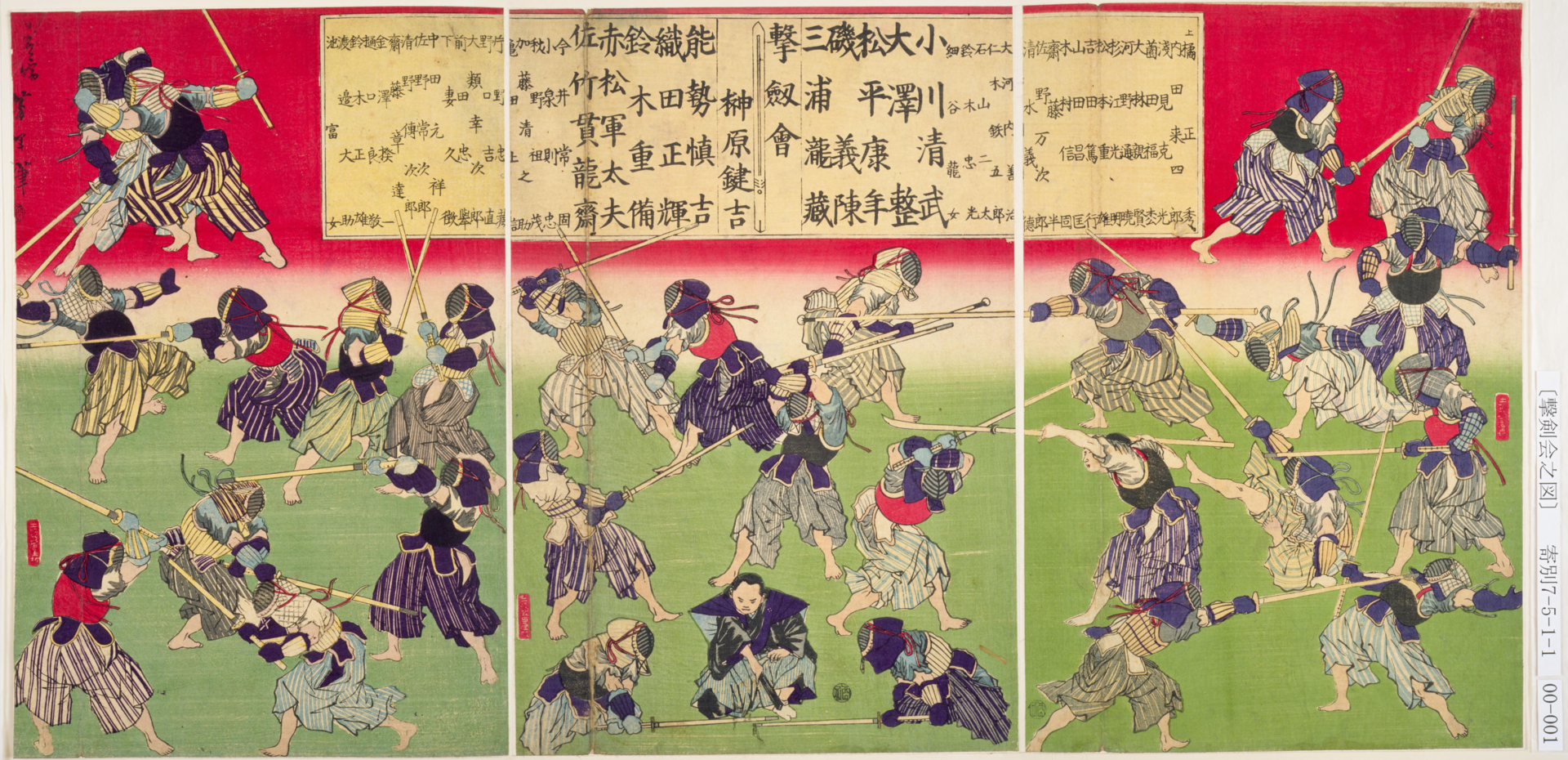

During this long peace, the samurai fought an increasingly desperate battle to keep their identities, their reasons for being. Mock battles were held at the foot of mount Fuji. Martial arts such as Kendo flourished in the absence of real war. The samurai would have a new purpose in life. The shogun’s government began to build the entire society on the rhetoric of warrior ideals. Bushido became not just the way of the samurai, but the way of Japan. The samurai themselves became the enforcers of social order. Ironically, it was only during this unprecedented time of peace that the first formal written version of the code of Bushido was written down by a samurai named Yamaga Soko. Yamaga’s most famous student and a romantic believer in the code of Bushido was Oishi Yoshio.

Martial Arts of Kendo

Oishi Yoshio led the famous raid of the 47 royal retainers of Ako in 1702, a story that has become one of the defining legends of Japanese culture, told and retold in countless books, plays, and movies. As the story goes, in 1701, lord Asano was publicly insulted by the lord Kira making him draw his sword. This was against the law in the shogun’s castle and he was forced in punishment to commit suicide. The samurai retainers of lord Asano, now Ronin, or masterless samurai, became beggars and drunkards for two years to alleviate suspicion while they plotted their revenge. Eventually, on a bitterly cold December night, they gathered and killed lord Kira in a daring attack.

Then the 47 ronin, carrying lord Kira’s severed head, walked slowly to the top of a hill, knowing that they had acted honorably and that they would probably very soon be dead. In classic Bushido tradition, they laid the head of their enemy on the grave of their lord. The actions of the 47 ronin put the government in a real quandary. Should they reward this sublime expression of the code of Bushido, or should they enforce the laws against vendettas that had kept the peace for so long? It was no longer classical Japan where the code of Bushido was the ultimate code. Now, the laws that kept the peace were much more important, and so they were forced to commit seppuku, ritual suicide, in the moonlight.

The 47 ronin were buried next to the tomb of their lord, and their graves have become something of a shrine to Bushido. But was the code of Bushido also laid to rest there? Well, yes and no. Soon after the death of the 47 ronin, centuries of peace had finally turned the samurai into petty bureaucrats. The samurai desperately tried to hold on to their remaining status, fighting skirmishes with swords against the guns of the new government conscript army. Some became so impoverished they were forced to do the unthinkable, sell their own swords.

Faced with the threat of western domination, the Japanese knew that they had to discard the old ways and adopt the new as quickly as possible. The samurai were ordered to cut off their top knots, their swords were confiscated, and their traditions and privileges were revoked. But the samurai had ruled Japan for more than a millennium. Bushido would be far from forgotten. After the samurai had disappeared, Japan’s new leaders designed their education system and social codes to preserve the values on which their warrior ancestors had prided themselves. They turned Masashige’s loyalty to the emperor into an ideal.

Today the brighter and nobler aspects of Bushido, the virtues of loyalty, honor, and perseverance live on. Part of the legacy of Bushido is the universal politeness and mutual respect so characteristic of Japanese society. Time and again the Japanese have turned to their samurai past in defining their national identity. In schools, sports clubs, and in the work place, group identities continue to hold sway, reflecting the loyalty of the samurai to his clan. Many modern Japanese are taught that the three great unifying generals together possess the ideal qualities of today’s business warrior. Nobunaga’s innovation, Hideyoshi’s diplomacy, and Tokugawa’s patience. These are all qualities which are embodied in an artifact that represents the feudal age of Japan.

The value of a sword is far greater than it’s material worth. It is a repository of history, it’s owner a temporary guardian of the spirits of past owners. He is thus obligated to cherish, respect, and maintain it for future generations, so that it can pass on to them the spirit it embodies. Just as the sword is the soul of the samurai, Bushido is still in many ways the soul of Japan.

Best Sellers

- Regular Price

- from $199.99

- Sale Price

- from $199.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $299.99

- Sale Price

- from $299.99

- Regular Price

-

$0.00

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $619.99

- Sale Price

- from $619.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $179.99

- Sale Price

- from $179.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $319.99

- Sale Price

- from $319.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $339.99

- Sale Price

- from $339.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $219.99

- Sale Price

- from $219.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $199.99

- Sale Price

- from $199.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $364.99

- Sale Price

- from $364.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $479.99

- Sale Price

- from $479.99

- Regular Price

-

$0.00

- Unit Price

- per